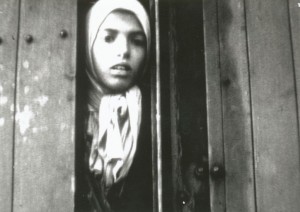

Taking a critical look at pictures that we assume are self-evident and true is not a challenge that we normally face. Nevertheless, the first step in the process of recognising genuine equality of rights involves finding out how representations of groups of people marked by some form of discrimination were historically produced and then reflecting on how many implicit prejudices are involved in them. Unless an effort is made to eliminate the presuppositions held by the social majority about what these “others” are like, legislation will make no difference. This is of course an uncomfortable task, because it brings us brought face to face with how far we are prepared to go to live in a society that is inclusive and just, and also a complicated one, because the objectives are not always obvious, even in the fight against discrimination. A case in point is the marked hierarchization of victims shown in the history of the way the Allied countries came to terms with the horror of the massive violence perpetrated under Nazism after the Second World War was over. A picture may help us penetrate the cultural underpinnings of our political attitudes. Among the best-known and most often reproduced photographs of Nazi terror is that of a young girl, her head covered with a scarf, looking apprehensively out of the wagon that will carry her off to Auschwitz, just moments before a soldier seals the door. In reality, this is not a still photograph, but a fragment of a short film that Rudolf Breslauer was forced to film; Breslauer was a Jewish prisoner from Westerbork, the transit camp that the train was leaving from.

For a long time it was taken for granted that the girl was Jewish, and on the basis of this supposition, the photograph became an iconic image of the Holocaust, summarising its cruelty by confronting us with the living gaze of a girl condemned to death. In the Netherlands, the departure point for those being deported, the picture of this girl became as well known as that of Anne Frank herself. In 1992, the journalist Aad Wagenaar researched her story in greater depth and discovered who the little girl was (Settela. Het meisje heeft haar naam terug, [Settela. The Girl Who Got Her Name Back] Amsterdam, De Arbeiderspers, 1995). Her name was Settela Steinbach and she was nine years old, a member of a Sinti gypsy family that was deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp in 1944. She and her brothers and sisters died there, as did their mother, whom a survivor remembers calling to the girl to put her head inside the wagon and not to hurt herself; their father, a violinist and trader, survived only until 1946.

The discovery that the person in the iconic photograph was not Jewish but Romani was met at the time with incredulity; in the early 1990s, Dutch society still felt so ashamed about what had happened to the Jews in their country that they did not regard it as right to compare the suffering of the Jews with that of other groups of people—gypsies, homosexuals, and so on—as if it lessened the enormity of or degraded the act of recognising the Jewish Holocaust.

This reaction is typical of the indifference to the Roma genocide that has, until very recently, been the most widespread attitude in Europe and America. The different treatments meted out to one set or other of the victims of Nazi racial persecution is demonstrated in both the historiographical delay and the well overdue official recognition. The history of the Roma genocide (Porrajmos) has taken much longer to be told than that of the Jews and other groups of people subject to reprisals under Nazism. Lack of interest, failure to recognize the victims, fear, the difficulties of documentation; all these factors conspired to create what, for a time, was rightly called the “forgotten Holocaust”.

the well overdue official recognition. The history of the Roma genocide (Porrajmos) has taken much longer to be told than that of the Jews and other groups of people subject to reprisals under Nazism. Lack of interest, failure to recognize the victims, fear, the difficulties of documentation; all these factors conspired to create what, for a time, was rightly called the “forgotten Holocaust”.

There is already, however, an ample bibliography on the greater and more systematic violence directed at the Roma people, which has the added virtue of being set in the context of the history of Gypsyphobia generally. Outstanding among these studies is the three-volume series comprising: Herbert HEUSS, Frank SPARING and Karola FINGS et al. (eds.) The Gypsies during the Second World War 1 From “Race Science” to the Camps, Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 1997; Donald KENRICK (ed.), The Gypsies during the Second World War 2 In the Shadow of the Swastika, Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 1999; and Donald KENRICK (ed.), The Gypsies during the Second World War 3 The Final Chapter, Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2006. In addition to these studies, there is also outstanding research by Guenter LEWY, The Nazi Persecution of the Gypsies, New York–Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000, who challenges some of the previous statements and comprehensively documents the various forms of persecution. For his part, Ian HANCOCK introduced the Romani term Porrajmos (“A Glossary of Romani Terms”, The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 45, No 2, 1997, pp. 329-344). See also, by the same author, “On the Interpretation of a Word: Porrajmos as Holocaust” (2006), and The Pariah Syndrome: An Account of Gypsy Slavery and Persecution, Ann Arbor: Karoma Publishers, 1987 (an electronic version is available).

Memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe murdered under national socialism

Memorial to the Sinti and Roma of Europe murdered under national socialism

Even more protracted has been the political and legal process of recognizing the Gypsies as victims of Nazism, of those responsible making financial compensation and the symbolic preservation of the memory of this group of people. The history of the monument raised in Berlin in remembrance of the Romani genocide is eloquent testimony to this procrastination. After denying, at the Nuremberg trials and in subsequent official statements, that the Gypsies had ever been racially persecuted during the Nazi period, the possibility arose, in 1982, of the German government acknowledging what had happened by erecting a memorial similar to those dedicated to other collective victims of the Holocaust. Yet it was only in 2012 that the monument was finally inaugurated.

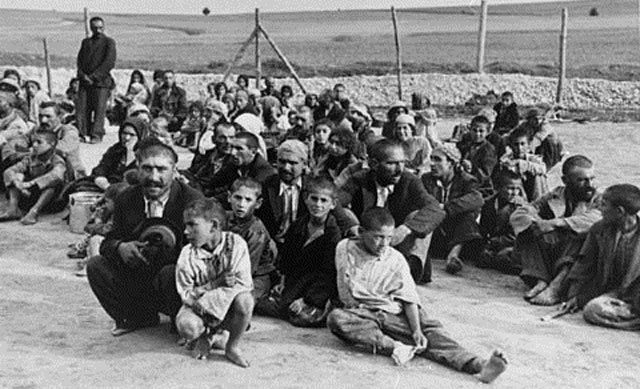

We have many pictures available to help us reflect on all this. When analysed with the appropriate instruments, the photographs taken by agents of Nazi racial terror, whether policemen, other kinds of civil servants or prestigious scientists, show us the other side of the story. Let us look at the images of the unrepresentable, images in spite of all, as Didi-Huberman put it, and let us not prolong the injustice of this historical and historiographical oblivion any further. And let us be bold in juxtaposing, alongside the localised suffering that they encapsulate, the historical reality, which is that Gypsies continued to be the targets of legal abuse, political persecution and social prejudice after Hitler had been defeated. Episodes such as anthropometric cards or the homecoming of Walter Winter, which are dealt with elsewhere in this blog, should help us read the images of what seems inconceivable to us.

unrepresentable, images in spite of all, as Didi-Huberman put it, and let us not prolong the injustice of this historical and historiographical oblivion any further. And let us be bold in juxtaposing, alongside the localised suffering that they encapsulate, the historical reality, which is that Gypsies continued to be the targets of legal abuse, political persecution and social prejudice after Hitler had been defeated. Episodes such as anthropometric cards or the homecoming of Walter Winter, which are dealt with elsewhere in this blog, should help us read the images of what seems inconceivable to us.

* The book by Aad Wagenaar has been translated into English by Janna Eliot and published, with an afterword by Ian Hancock, as Settela, Five Leaves, 2005. The film-maker Cherry Duyns used Wagenaar’s book as the basis for her 1994 documentary (Settela, gezicht van het verleden (1994).