El día 16 de mayo se recuerda internacionalmente la acción de rebeldía y resistencia de las familias gitanas que, prisioneras en el campo nazi de Auschwitz, se enfrentaron a sus carceleros cuando estos pretendieron conducirlas masivamente a las cámaras de gas. Ayer, asociaciones romaníes de todo el mundo volvieron a traer a nuestra memoria estos hechos ocurridos hace 64 años.

Una colaboración importante en la construcción de esta memoria es el libro de Toby Sonneman, que recoge de primera mano testimonios de supervivientes gitanos del holocausto: Shared Sorrows. A Gypsy family remembers the Holocaust (Hatfield, University of Hertfordshire Press, 2002). La autora, hija de un judío que huyó de Alemania y cuya familia sufrió igualmente la persecución nazi, parte del reconocimiento de su implicación subjetiva en la historia que quiere narrar. Lo hace con honestidad y modestia. Y desde este lugar tan especial, recupera con realismo y respeto el dolor de quienes quedaron marcados toda su vida por el sufrimiento que el nazismo -y el posnazismo- les infligió.

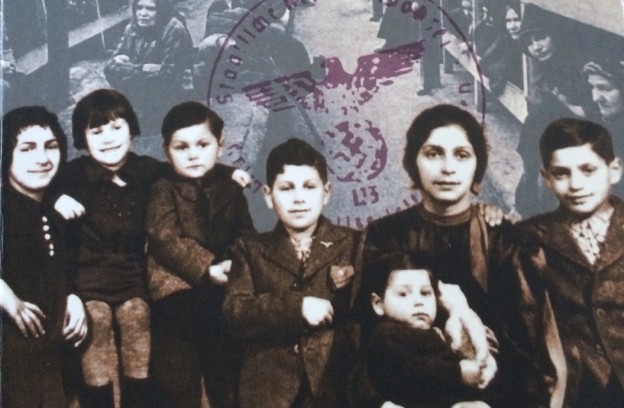

Se trata de una historia coral, gracias a la ayuda de Reili Mettbach, gitana sinti alemana, quien la introduce en su familia y le presenta a miembros de la misma que, de una manera u otra, han vivido el genocidio nazi: hay quien fue esterilizado a la edad de doce años, quien sobrevivió a un campo de exterminio, quien se fugó de otros campos de trabajo forzado, quien recuerda cómo de niño su hogar se convirtió en centro de reunión de todos los gitanos que buscaban refugio…

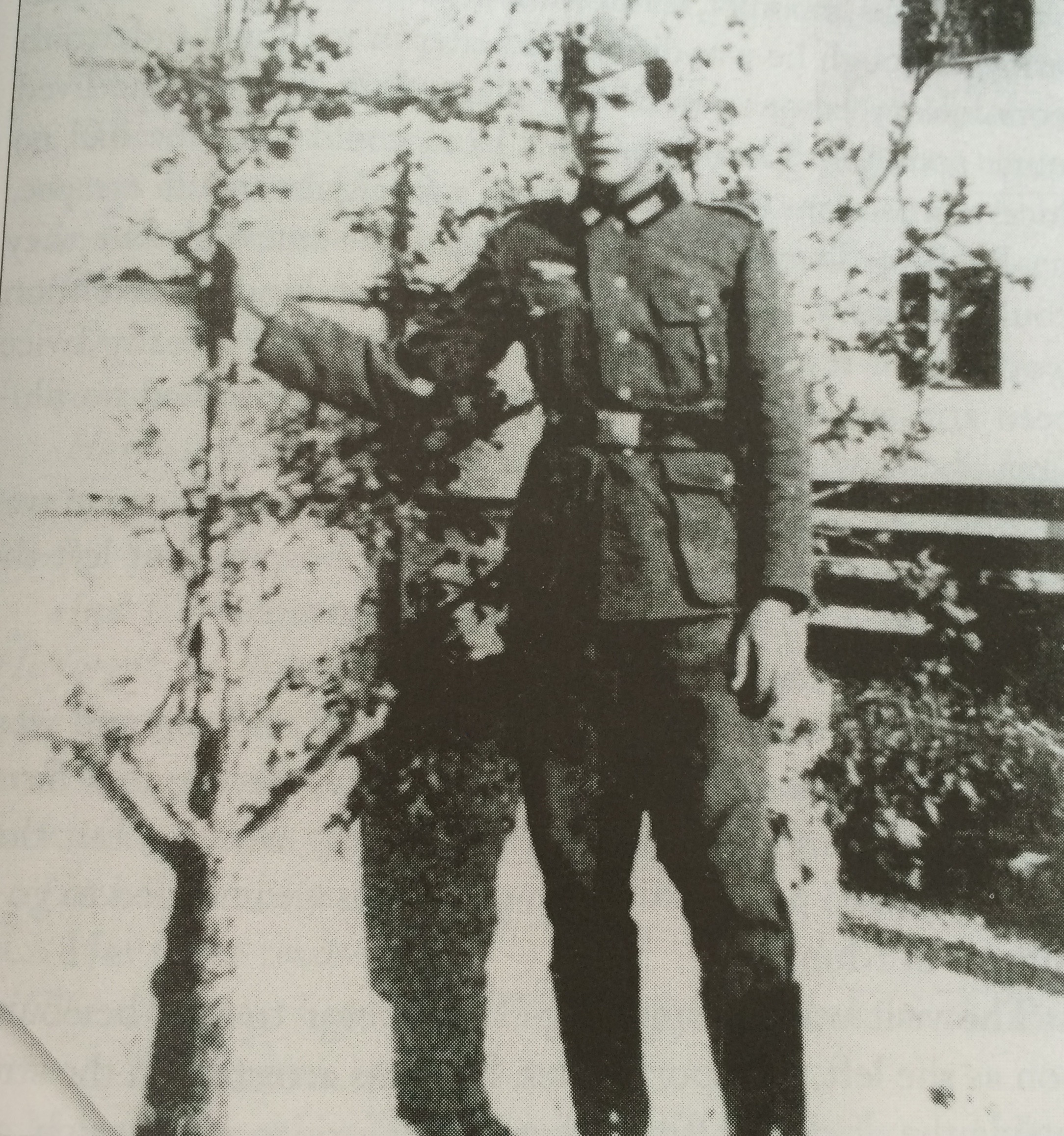

La sensibilidad de Toby Sonneman para respetar las memorias fragmentadas se extiende al reconocimiento de la especificidad del holocausto romaní, tan grave como el judío en términos demográficos relativos o más, incluso, por lo limitado de las acciones de reconocimiento y reparación. Johan -Hamlet- Mettbach, 1941

Johan -Hamlet- Mettbach, 1941

Quien se asome a su libro se sorprenderá con la historia una familia asentada en Alemania desde hace más de cuatrocientos años, varios de cuyos miembros servían incluso en el ejército del que creían “su” país –hasta que la política racial del régimen nazi los depuró-, cuya imbricación en su vecindario no les libró de la consideración de “asociales” y apátridas con la que se estigmatizó genéricamente a los gitanos europeos.

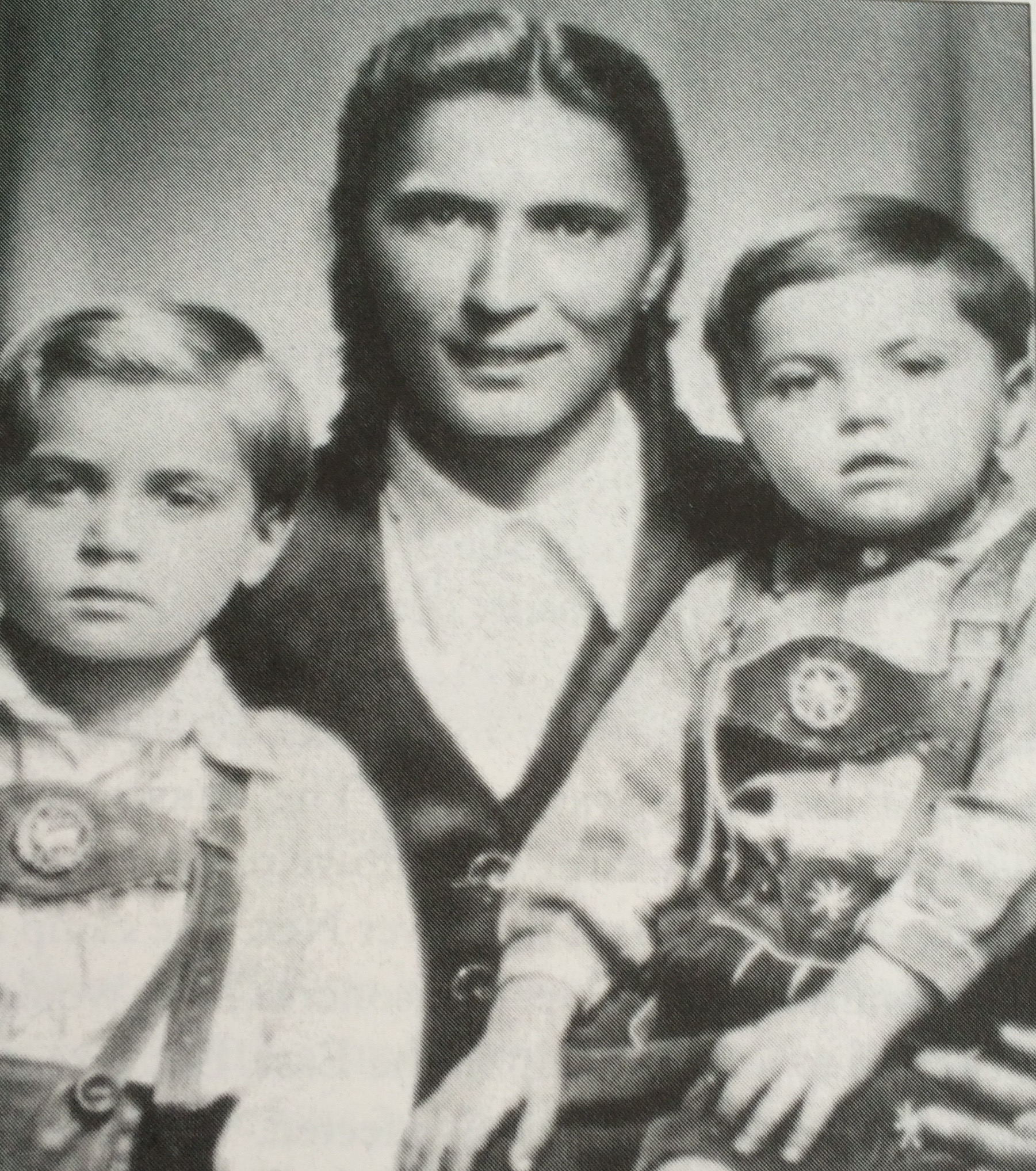

Entre las historias particulares que componen este gran relato coral, destaca la valentía con la que habla Rosa Mettbach, quien tenía 14 años cuando comenzó su periplo a través de cárceles, campos y escondites. Sobre un álbum de fotos familiar, señala y nombra a hermanas, sobrinos y otros parientes asesinados. La hermana de Rosa, con sus dos hijos, muertos en Lódz

La hermana de Rosa, con sus dos hijos, muertos en Lódz

Y cuenta también su propia historia, que encadena episodios de fugas y resistencias. Entre ellos, destaca el relato de la tercera deportación que sufrió, nada más ser madre y desposeída de su hijo. Detenido su transporte para recoger más prisioneros en Viena, donde había vivido de niña, recuerda cómo un policía que conocía a su familia le dijo con tristeza: “No puedo hacer ya nada más por ti, no puedo hacer nada – vas a Auschwitz”. Solo añadió, “Y tu madre murió en Litzmannstadt (Lódz)”, (pp.65-66). Rosa se separó de ella para escapar del tren que la conducía con sus hermanas y hermanos al gueto polaco que compartieron judíos y gitanos. No volvió a verlos a ninguno con vida.

Su voz habla de resistencia. También, del dolor de sobrevivir.

* El United States Holocaust Memorial Museum tiene recogidas y accesibles en su web una serie de entrevistas a testigos romaníes de la persecución nazi realizadas por Gabrielle Tyrnauer, consciente de la urgencia de recoger los testimonios cada vez más escasos de estos supervivientes

** Las fotografías de esta entrada proceden del libro Shared Sorrows, de Toby Sonneman.

A Commemoration of Romani Resistance

May 16th was international Romani resistance day, a day that commemorates the act of rebellion and resistance of Gypsy families imprisoned in the Nazi camp of Auschwitz, who fought back against their guards when they tried to round them up and send them en masse to the gas chambers. A few days ago, Romany associations around the world recalled those events of 64 years ago.

An important contribution to the construction of this memory is the book by Toby Sonneman, who collected first hand testimonies of Gypsy survivors of the Holocaust: Shared Sorrows. A Gypsy Family Remembers the Holocaust (Hatfield: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2002). The author, the daughter of a Jew who fled from Germany and whose family also suffered persecution by the Nazis, starts by acknowledging her subjective involvement in the story she wants to narrate. She does so with integrity and modesty and, from this very special position, she recuperates with realism and respect, the pain of all those whose lives were marked forever by the suffering that Nazism—and Postnazism—inflicted on them.

The story is a choral one, thanks to the help of Reili Mettbach, a German Sinti Gypsy, who introduced the author to her family and members of it who, in one way or another, had experienced the Nazi genocide. There was someone who had been sterilized at the age of twelve, someone who survived an extermination camp, someone else who escaped from other forced labour camps, and yet another who remembered how his home became a meeting place for all Gypsies who were seeking refuge, and so on.

Toby Sonneman’s sensitivity in respecting the fragmented memories extends to recognition of the specific nature of the Romani Holocaust, which was as appalling as the Jewish in relative demographic terms, or even more so, because of the limited acts of recognition and reparation.

Readers will be surprised to learn about a family that had been settled in Germany for more than four hundred years, several of whose members even served in the army of what they believed to be “their” country—until they were purged by the racist policies of the Nazi regime—and despite them being completely integrated in their local neighbourhood, this did not prevent them from being stigmatized as “asocial” and stateless along with the rest of European Gypsies.

Among the individual stories that make up this great choral account, the one that stands out tells of the bravery and courage of Rosa Mettbach, who was fourteen when her odyssey through prisons, camps and hiding places began. From a family photograph album, she picks out and identifies sisters, nephews and other dead relatives by name. She also tells her own story, which is a series of episodes of escape and resistance. Another that stands out is the tale of her third deportation shortly after she had given birth, when her son was taken away from her. When the vehicle stopped in order to pick up more prisoners in Vienna, where she had lived as a girl, she recalls a policeman who knew her family saying sadly to her: “I can do nothing for you, more. I can do nothing for you – you are going to Auschwitz”. He simply added, “And your mother died – in Litzmannstadt (Lodz)”, (pp. 65–66). Rose left her to escape from the train that was taking her brothers and sisters to the Polish ghetto shared by Jews and Gypsies. That was the last time she saw any of them alive.

Her voice, recorded with affection by Toby Sonneman, speaks of resistance. And of the pain of being a survivor.

- The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum has gathered together and made available on their website a series of interviews with Romany witnesses of the Nazi persecution, carried out by Gabrielle Tyrnauer, conscious of the urgent need to collect the increasingly scarce testimonies of these survivors

- Photographs from Shared Sorrows, by Toby Sonneman.