Sometimes, the most “innocent” images are the most dangerous.

Confirmation of this statement can be found in the children’s stories that have for many years employed characters taken from the world of the gypsies in order to indoctrinate children and teach them obedience. During the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, some of the teaching designed to inculcate the values of the official culture and promote family discipline was carried out through stories in which rebellious children—those who dared to disobey their parents and leave their comfortable homes—frequently ended up being stolen by bands of gypsies and vanishing into thin air.

These kidnappers, described as living on the fringes of civilized society, represented all the evils of barbarism—pagan, immoral, uncouth and criminal—in contrast to the alleged virtues of the national culture. Heading the long list of illegal actions attributed to gypsies in these stories, that of child stealing is a hackneyed theme that appears over and over again in European children’s literature.

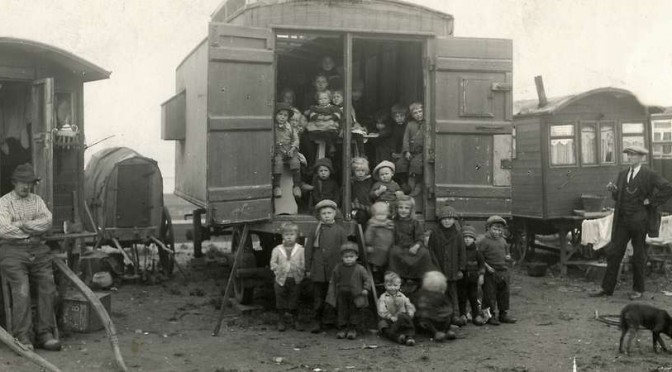

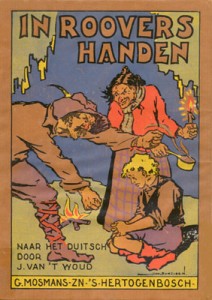

Into the hands of robbers, 1922

Into the hands of robbers, 1922

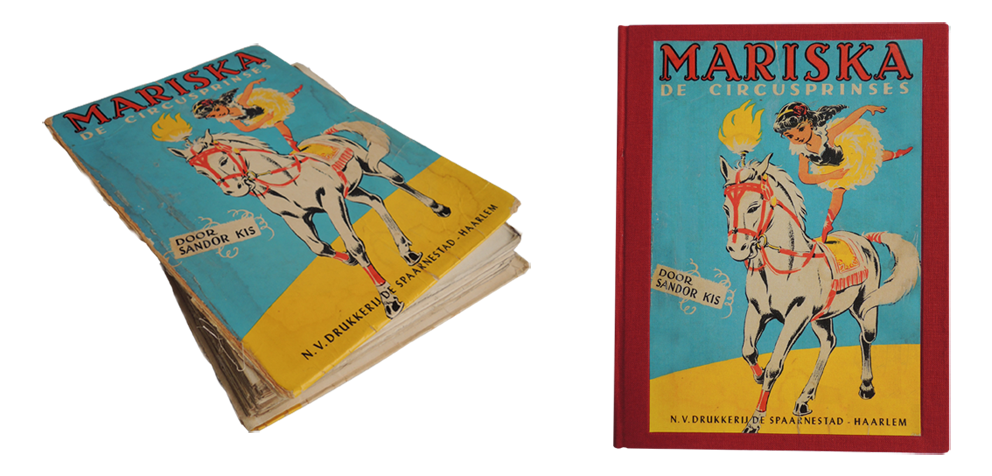

Mariska is just one of the most famous of these girls in fiction stolen by the gypsies, the sweet daughter of a well-to-do man who, one unfortunate day, came face to face with danger because she failed to take care when out riding her horse:

An ugly old crone looked her straight in the face.

“Ha, ha, ha!” the old crone laughed, as a huge tooth in the front of her mouth bobbed up and down.

Now she looked like a large bird of prey that had caught a tiny bird.

She immediately stuffed a ball of cloth in the little girl’s mouth and tied a rag around it.

Soon afterwards, they arrived at a caravan. There, they took all Mariska’s pretty clothes off and dressed her in some ugly dirty disgusting rags. Her face, hands and feet were smeared with grime, and her pretty clothes were then soaked in oil and burned. It was awful. And that woman was there and did not stop cackling with laughter. Every now and then, they would pull poor Mariska’s hair.

“Haven’t we made you into a lovely beggar? Go back to your father’s farm now, and you’ll soon see, they’ll call you a filthy gypsy and set the dog on you.”

The gypsy children were soon tormenting Mariska, pulling her hair, and punching and kicking her. And what upset Mariska most of all was their rudeness. They called her really nasty things. Then they grabbed Mariska again, stuffed a ball of cloth in her mouth and shoved her into a large wooden chest.

“Right, that’s that,” said the man. We’ve often taken things over the border this way.

Mariska, 1955Sandor Kis, Mariska, Princess of the Circus (Mariska de Circusprinses), 1955, .

Mariska, 1955Sandor Kis, Mariska, Princess of the Circus (Mariska de Circusprinses), 1955, .

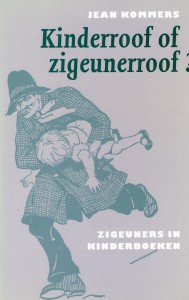

Jean Kommers, an anthropologist interested in processes of image formation, especially the construction of images of cultural alterity, studied this and four hundred other similar stories that were published in books for young children and teenagers in the small country of Holland between 1825 and 1980. To do so, he employed the discipline of Imagology, which was used to good effect in academic circles in northern and central Europe to analyse the role of images in processes of national identity formation, but making the focus of his study representations that affected marginalized or dominated social groups. In 1993, he published a book about the image of gypsies in children’s literature, Kinderroof of Zigeunerroof? Zigeunners in kinderboeken [Stealing Children or Stealing Gypsies? Gypsies in Children’s Literature] (Utrecht: Van Arkel), a revised edition of which is now being prepared in Spanish. Kinderrroof of zigeunerroof?

Kinderrroof of zigeunerroof?

In this study, Jean Kommers came to some important conclusions that remain valid twenty years later, among them, that the “innocent” and “trivial” literature of children’s stories has played a substantial role in disseminating images that convert gypsies into the dregs of society, a group that does not deserve to have civic rights. The title of Kommers’ book sums up his main conclusion, since it alludes to the “stealing” myth, at the same time as it turns it round. Through the accumulation of negative stereotypes about them, children’s literature has robbed gypsies of the opportunity to be seen as respectable people by successive generations of adolescents.

Accusing them of crimes such as child stealing is analysed in terms of its symbolic value, as marking a dividing line that categorically separates some groups from “others”. The attention paid to the structural features of this type of literature—especially the repeated recourse to binary oppositions (black/white, civilized/barbarian, Christian/pagan)—enables the author to point out the hidden foundations and social effects of expressions of xenophobia that can also arise in the present. In parallel to all of this, Kommers’ work suggests that “these ‘innocent’ books, whose stated intentions were to teach children about the importance of behaving like good Christians in life, were also in fact—more than anything else—books about power, (…) the power of the dominant society over another dominated one. They were about social inequality and played an important part in prolonging it”.

The social significance and scientific originality of Kommers’ study mean that it certainly deserves to be recuperated. This is the purpose of the Spanish edition, which is to be published before the end of 2015. The Editorial Universidad de Sevilla [Seville University Press] has taken on the translation from Dutch of this book, which had a small print run and scant circulation when it first came out, and will publish it, under the supervision of María Sierra, in its Colección de Geografía e Historia [Geography and History Collection]. The new book not only includes the eminently useful study originally published in 1993, but also adds two texts that revisit it and bring it closer to the present (social and academic) state of affairs. On the one hand, the author himself contributes an essay entitled “Twenty Years Later…” in which he subjects the results of his work to criticism and discussion, indicating the need to add other perspectives of a historiographical kind to the anthropological approach employed originally. María Sierra, for her part, endeavours to respond to the challenge in her “Introductory Study”, in which she explains the origin and meaning of this unusual Hispano-Dutch publishing venture.

As Jean Kommers points out in his exercise in self-criticism, while we do need to ask about changes in the interpretation of symbols inscribed within very persistent images, it is also worth reflecting on the fact that the representations that most gadjé have of the gypsies do not come from direct contact with them, not even in Spain, a country with more than half a million gypsies and a growing number of self-representation associations in the roma community. Recent initiatives designed to review and dissolve stereotypes, directed at very diverse segments of official culture, from the mass media to the Royal Academy of Language, still have plenty of work ahead of them.

Past and present, minority and minorities; the study of representations also serves to illuminate relations between phenomena of marginalization and social injustice at different times and with different protagonists. The words this summer of the Mayor of the small Austrian town of Grosskirchheim refusing to give shelter to refugees, look as if they have been copied from one of the stories about gypsies analysed in Kommer’s book (Janse: Er komen vreemde logeergasten [Strangers are coming to stay] 1979):

This is our town. We are used to leaving our doors open at night. Because there are no pickpockets or thieves around here. All that will change when those shelters are opened, and we don’t want that to happen.

(NOS, 14-8-2015)

“The refugees are the new gypsies”, has stated the Hungarian philosophe Gaspar Miklós Tamás in view of recent events. His remark is the best way to conclude this post about a book concerned with the processes of image formation and the maintenance or transfer of their symbolic contents. Representations of alterity and social marginalization form a two-way circuit.

And not forgetting, at the same time, that there are a good many “former” gypsies among the refugees.

(*) In this text, the word gitano [gypsy] is used intentionally and for various reasons that we would like to clarify. First of all, because this is the term used in the literature that we are referring to. Secondly, because, in spite of being aware that the word gypsy has a strong pejorative component in English and other languages, which makes those who are addressed as such reject it in favour of Rom (Roma, Romani), in Spanish, the term gitano has a positive meaning from an identitarian point of view for those who are proud to call themselves such. This is why this entry uses the term differently depending on the linguistic context.