This woman of stunningly light eyes was called Teresa Gabarre.

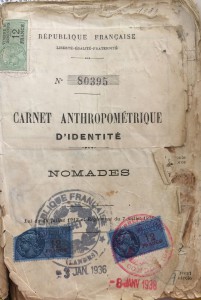

So says, at least, her “anthropometric card”, a document required by French State to all nomad people, ever since a law passed in 1912 and still applicable in 1968 made it mandatory. This is an example of how were treated in liberal and democratic states, before and after the Second World War, a largest transnational Roma community who found in trip its economy and its way of life.

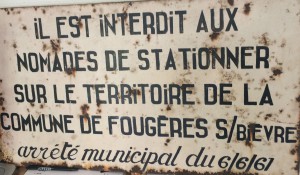

The criminological obsession of western culture about subjects considered “inner enemies” –these asocial ones who allegedly threatened the order- could be materialized in this kind of documents.

The criminological obsession of western culture about subjects considered “inner enemies” –these asocial ones who allegedly threatened the order- could be materialized in this kind of documents.

In France, these cards incorporated frontal and side-face photographs -with an evident police appearance-, apart from many information (name, nickname, home country or birth date), and anthropometric details: waist and bust height, head width and height, bicigomatic width, right ear length, middle fingers and left aural length, left elbow length, etc. Of course, fingerprints too (for further concerned observations about the implicit criminalization, refer J. P. Clebert: Les Tziganes, 1961)

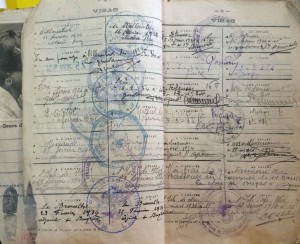

There were individual and collective cards, the latter ones were under household’s responsibility. So every time a romani person wanted to come into o leave any location (not even the country), he or she ought to request the permission to the police. Teresa’s card has ¡76! pages of cramped grids filled with the visas she needed (or she managed to get) from 1934 to 1939.

managed to get) from 1934 to 1939.

During Second Word War, Nazi regime applied to Roma people the same proceedings as Jews: detentions, ghettos, concentration camps, medical trials and extermination; nevertheless, their recognition as Holocaust victims would have to await decades. After 1945, survivors could not do anything else but trying to remain unnoticed, since, either in defeated Germany or victor’s territories, legislation which made “gypsies” subjected to the persecution continued in force, regardless of human suffering caused by racial persecution.

Given the stagnation of the legislative liberal logic, imagination was the way explored by the first Romani activists. Anthropometric card shackled its bearer, but an alternative document would on the other hand try to free him. Ionel Rotaru, Communauté Mondiale Gitane founder, came up with a passport devised as a guarantee of legal nomadism, an identity card that assured to these landlessness people the political recognition needed to cross borders. Only the bands colored with the gypsy flag differentiated them from common passports: by the time some Polish Roma were arrested in France in 1970 for using these documents, Rotaru’s association had already been forbidden by De Gaulle years before.

Some ideas, however, have more scope than the law that forbids them.

Find this post in Spanish (Translation by Begoña Barera)