«I use the word “gypsy” because it is the operative term used in the children’s literature to be discussed. Also to stress that it concerns an idea, a construction pretending to represent ‘real’ people. Therefore this fiction contributed to attitudes that really affected (and often disfigured) the lives of people.»

With this powerful statement our colleague Jean Kommers opens a lecture about the role of the «gypsies» in children´s literature at the Jewish Historical Museum of Amsterdam (April 21, 2018). His lecture offers a dialogue with the study about Jews in Children’s books by Ewout Sanders (Levi’s eerste kerstfeest. Jeugdverhalen over Jodenbekering, 1792-2015 [Levi’s first Christmas, Juveniles about the conversion of Jews). PENDARIPEN provides a summary of this interesting activity, that will take place on April 21 (2018).The lecture is mainly about an idea which in juveniles is related in particular with “gypsies”: the stealing of children. A booklet edited in 1993 (and re-issued in Spanish in 2016) was called “Stealing of Children, or Stealing of Gypsies?”. Main thesis was that rather than “gypsies” are stealing children, the various authors are ‘stealing’ “gypsies” to (mis)use them for a range of goals. The stories – often openly about didactic ideas – in fact are about power and inequality.

The approach closely analysed (over a period of about two centuries) what exactly is happening when a child is stolen (in the narratives, of course). This resulted in discovering an intricate pattern comprising symbolically meaningful oppositions, forms of identity change, expressions of power and inequality, to mention just a few aspects. Such an analysis has not been executed since then (Compare e.g. Hans Richard Brittnacher in Petra Josting u. A. : “Denn sie rauben sehr geschwind jedes böse Gassenkind”; Göttingen, Wallstein Verlag, 2017: 56-78. See also David Mayall: Gypsy Identities: 1500-2000.).

It is payed special attention to Sanders’ observation that it would be interesting to compare conversion-tales concerning Jews with those concerning other peoples, like Sinti and Roma (Sanders, p. 127). Many children’s narratives about “gypsies” contain conversion-tales, some written by the same authors Sanders mentioned in connection with Jews. For instance Ida Keller: under the title Bianca, het verkochte zigeunerkind [Bianca, the sold gypsy-child – 1907] she wrote a very stigmatising tale about “gypsies”.

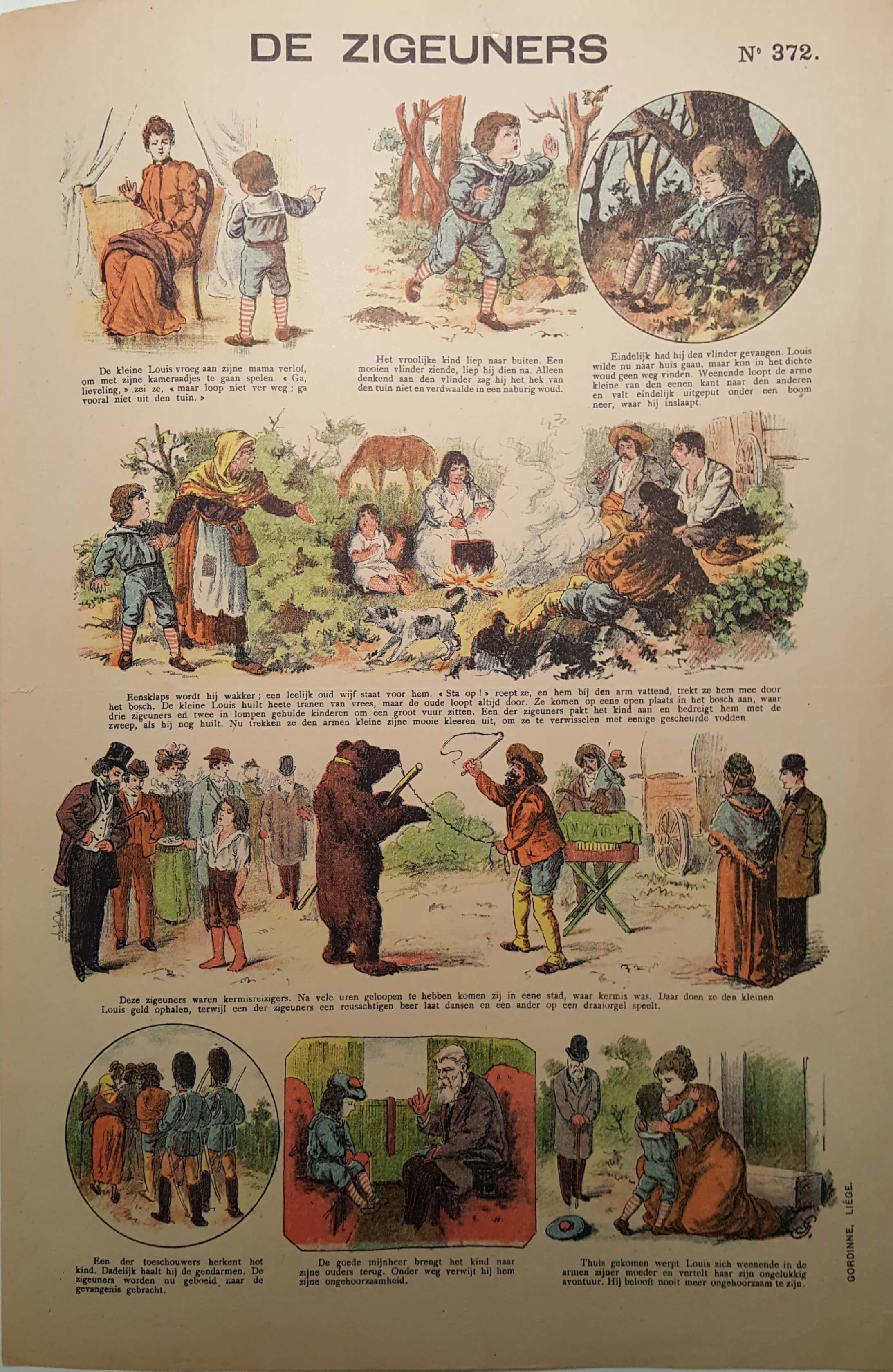

In children’s tales sometimes – as far as Dr. Kommers could find mainly in early German juveniles – “gypsies” are discussed in relation to Jews. In those cases the “gypsies” are described much more unfavourably than the Jews. Centsprent Zigeuners in coll. Arie van den Berg UB. Royal Library (The Hague)

Centsprent Zigeuners in coll. Arie van den Berg UB. Royal Library (The Hague)

In conversion tales about “gypsies” the conversion is always limited to individuals. There are some tales inspired by missionary attempts but also these as a rule end by describing individual conversions. In only one juvenile tale he has found explicit references to those missionary attempts: Agnes Strickland mentions Hoyland and Crabb in her Tales of the School-Room (1835: 113-114). However, although in narratives like these there are conversions of individual “gypsies” to Christianity, in fact also these primarily serve to educate the little readers, rather than boasting “gypsy”-conversions or suggesting that the “gypsies” can change. Just as little as Crabb c. s. were successful, concerning the “gypsies” these stories often end in minor key. Besides, those “gypsies” that are converted, always have some special characterizations. Like the protagonist in one of the oldest narratives: Madge Blarney, the Gipsey Girl (1797). Madge had “a reflective mind” which set her already at the outset apart from ‘the rest of the gang’. In most tales the converted child proved to be a stolen child.

In his study Sanders discovered discriminatory texts still being published and he wondered: how is it possible that these texts are still in use? This question is also relevant in relation to “gypsy”-narratives. An early 19th century text like Von Schmid’s Heinrich von Eichenfels (1817) proved still to be in use at some kinds of Sunday Schools in the United States. One reason might be that readers do not notice the discriminatory remarks at all. This became clear when studying contemporary reviews of that kind of booklets (See Jean Kommers & María Sierra: Robo de niños, o robo de gitanos? Gitanos en la literatura infantil. Editorial Universidad de Sevilla, 2016: 199-212.)

Many academics studying children’s books about “gypsies” are inclined to evaluate from their own perspectives. Sometimes this is quite useful (and understandable, like in German studies reflecting the trauma of the Nazi-time). But to understand the contemporary effect of image formation, one should also try to get insight into the difficult question of historical interpretations.